October 2022 Newsletter

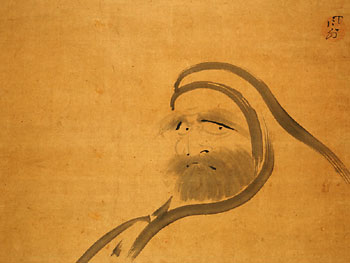

Forthcoming Events: The Festival of Great Master Bodhidharma

On Saturday the 1st of October we will be celebrating the Festival of Great Master Bodhidharma. Bodhidharma is an important figure within Zen, as he is credited with bringing the meditation school of Buddhism from India to China. His emphasis on “pure meditation”, and the need to spend time “just sitting” facing a wall, are still central to our tradition. This festival is an opportunity to celebrate the life of Bodhidharma and to focus on some of his important teachings.

In addition to welcoming visitors to the temple for the festival (please book in advance), we will also be holding the festival over zoom so that Lay Sangha members can join in from where they are. Full details of the festival day have been sent out by email to Lay Sangha members.

This festival day will run from 10am to 4pm, with the Festival and Dharma Talk both in the morning so that people can come just for those if they would prefer. There will then be the option to stay on for a bring-and-share lunch and an afternoon of meditation, followed by tea and biscuits and an opportunity to ask questions.

Recovering from the drought

After a very hot and dry couple of months in July and August it was welcome relief to have some rain in September. Much of our lawn had died off, except where it was shaded by the trees in the park, but is now growing back strongly, and in need of cuttting again!

Buddhist Stories

There are many stories in Buddhism, from the time of the Buddha onwards, and they are very helpful in illustrating aspects of the Buddha’s teaching and Buddhist practice.

The blind people and the elephant

In this story, the Buddha uses the image of blind people meeting an elephant for the first time, but only feeling a part of it, to point out that we so easily think that the whole of the world, and the whole of Buddhist practice, must be just the same as our own experience of it. It is this story that Dōgen refers to in Rules for Meditation when he says, ‘do not spend so much time in rubbing only a part of the elephant’.

Once, when the Buddha was staying near the city of Sravasti, some of his disciples came to him and said, "Lord Buddha, there are many wandering hermits and scholars living here in Sravasti, all from different religious groups, and they are constantly arguing and quarrelling. They all have different views and opinions on what they consider to be the most important questions of the day. They argue, for example, about whether the world will go on forever or whether it won’t, and they argue about whether the universe has any limits, or whether it doesn’t. In fact, it seems that almost anything that they talk about, they have different views and opinions on. They are always disagreeing, and their disagreements turn into conflicts, and because of this they are not able to get along with each other. Lord Buddha, how should we think about these quarrelling people?"

The Buddha answered them with this story:

A long time ago there was a mighty ruler who lived in this very city of Sravasti. One day that wise ruler summoned one of his chief ministers, and gave this instruction, ‘Come, chief minister, go out into this great city of Sravasti, and gather together in one place all the women and men who live here who were born blind. And when they are all gathered together, I would like you to show them … an elephant!’

The minister replied, ‘Very good, Great Ruler’, and went off to put this unusual request into practice. Once the minister had assembled a group of blind people, all in one place, a large elephant was brought in, and the minister said to them, 'Good men and women, I am now going to introduce you to … an elephant.' Of course, none of them had ever seen an elephant, so they didn’t know what it was going to be like.

Then the minister took one of the blind people up to the elephant, and let them feel the head of the elephant, and the minister said to the blind person that this was an elephant. Then the minister took another person up to the elephant, and let them feel one of the ears of the elephant. Similarly, one after another, one of the blind people was presented with the tusk of the elephant, another with the trunk, another with the side, and so on with the foot, the tail, and the tuft at the very end of the tail. To each of these people the minister said that this was an elephant.

When the blind women and men had all felt the elephant, the wise ruler went to each of them in turn and said to them, ‘Well, blind person, have you now met an elephant? Tell me, what sort of a thing is an elephant?’

Then the person who had only felt the elephant’s head answered, ‘Great Ruler, an elephant is like a pot.’

And the one who had only felt the elephant’s ear replied, ‘Great Ruler, an elephant is like a large fan.’

And the one who had only felt the elephant’s tusk replied, ‘Great Ruler, an elephant is like a mighty curved sword.’

In just the same way, the one who had only felt the trunk said that an elephant was like the large branch of a tree; the one who had only felt the side of the elephant said that it was like the mud wall of a house; the one who had only felt the foot said that an elephant was like a stone pillar; the one who had only felt the tail said that an elephant was like a snake; and the one who had only felt the tuft at the very end of the tail said that an elephant was like a brush.

When the blind people heard how each other had described what an elephant is like, they all began to quarrel, shouting at each other ,‘An elephant is not like that, it is like this’, 'No, it isn’t!', 'Yes it is!' On and on they argued, until eventually they came to blows over whose description of the elephant was correct.

When he had told this story, the Buddha then said to his disciples:

Obviously, we can see that each of these people was describing their own experience of the elephant. Each one was correct in describing what they had felt, but they didn’t realise that they had felt only part of the elephant. They assumed that the whole of the elephant must be like their bit, and so they argued with each other about who was right.

The wandering hermits and scholars that you have met, are just like this. They each have their own experience of the world, and like the blind people, they think that all of the world, and everyone else’s experience of it, must be just like that. Each is attached to their own view, and they’re convinced it’s the only correct one, and so they argue and quarrel with each other, and cannot get along.

We all tend to be attached to our own view of the world as well, the Buddha said. It is so easy to be like the blind people who have rubbed only a part of the elephant. But if we are wise enough to see that we only have part of the picture, then we are more willing to listen to what others have to say. We can each learn from the others’ experience, and respect their different understanding, and then there is no need for us to argue and quarrel. If we can stop arguing, then we have a much better chance of getting on with each other, and of living well together.

Alms Bowl Requests

Donations of Food

Offering food is a traditional way to support a monk, and all donations of vegetarian food are most welcome. In particular:

- porridge oats

- peanuts or other nuts

- peanut butter

- fresh fruit and vegetables (except garlic or peppers)

- dried herbs

- cheese, eggs and yoghurt

Any other suitable items would also be appreciated.

Donations

The temple is dependent on donations for its continued existence, and any financial support you are able to offer is greatly appreciated. Details of how to offer support can be found on the Donations page of the website.

All donations are received with gratitude