September 2023 Newsletter

Forthcoming Events:

The Festival of Avalokiteshwara Bodhisattva

On Saturday the 9th of September we will be celebrating the Festival of Avalokiteshwara, the Bodhisattva of Compassion. The name Avalokiteshwara is Sanskrit (Japanese: Kanzeon, Chinese: Kwan Yin, Tibetan: Chenrezig), and means “The one who hears the cries of the world”. To live with compassion is to hear the cries of suffering within ourselves and within all beings, and to be willing to respond, and the festival will focus on this centrally important aspect of Buddhist practice.

During the festival a wide variety of different images of Avalokiteshwara are placed around the walls of the meditation hall, and we circumambulate the hall and bow to each image as we pass it. This symbolises the fact that compassion can appear in many different forms, sometimes in a way that we least expect, and that if we want to know stability and contentment in our lives we must accept, and bow to, all these different appearances of the nature of reality. This is one way in which we ourselves express compassion for all living things.

In addition to welcoming visitors to the temple for the festival (please book in advance), we will also be holding the festival over zoom so that Lay Sangha members can join in from where they are. Full details of the festival day will be sent out by email to Lay Sangha members prior to the festival.

The festival day will run from 10am to 4pm, with the Festival and Dharma Talk both in the morning so that people can come just for those if they would prefer. There will then be the option to stay on for a bring-and-share lunch and an afternoon of meditation, followed by tea and biscuits and an opportunity to ask questions.

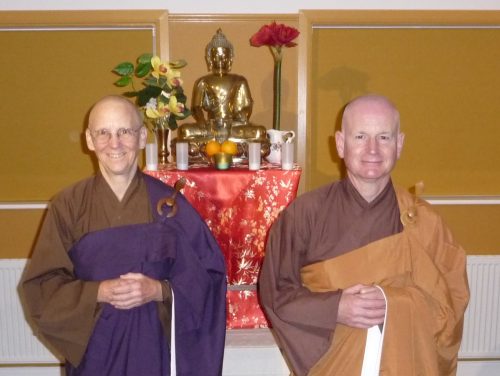

Visit from Rev. Vivian

It was lovely to be able to welcome Rev. Vivian Gruenenfelder to the temple for a visit in early August. Rev. Vivian is an American monk of our order and is usually resident at Still Flowing Water Hermitage in California. The hermitage is located in Dutch Flat, a tiny village in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, 25 miles east of Auburn, California.

Rev. Vivian was able to visit for several days, and joined us for all of the regular temple events that happened during that time, including a Thursday evening Basic Buddhism Evening, the Festival of Great Master Dōgen on the Saturday, and our Sunday Meditation Morning.

Rev. Vivian kindly gave a Dharma Talk at the Festival, which is now available to listen to or download on the temple website.

During Rev. Vivian’s visit, Rev. Aiden and Rev. Vivian also travelled down to Cambridge to visit Rev. Master Leandra. We were able to spend several hours with her and we had lunch together at a cafe close to where she lives.

Following her stay at the temple Rev. Vivian spent a few days with Rev. Alicia at Sitting Buddha Hermitage in Derbyshire, and then travelled up to Throssel Hole, where she will be spending the majority of her time in the UK. She flies back to the US in early October.

Buddhist Stories

There are many stories in Buddhism, from the time of the Buddha onwards, and they are very helpful in illustrating aspects of the Buddha’s teaching and Buddhist practice.

Shariputra meets a Goddess

Part 1: Flowers of non-attachment

This story is from the Vimalakirti Sutra, a scripture in the Mahayana Buddhist tradition which was perhaps written at the end of the 1st century CE. The central character is the lay person Vimalakirti, who is portrayed as being profoundly enlightened, having trained very deeply in Mahayana Buddhism. The scripture uses various different characters and encounters, some of them quite humorous, to highlight the difference between Mahayana teachings and what the Mahayana tradition sees as the more narrow understanding of early Buddhism, which is often represented by the characters of the Buddha’s disciples.

At the point in the scripture where this story occurs, a vast assembly made up of “eight thousand bodhisattvas, five hundred of the Buddha’s disciples, and hundreds of thousands of heavenly beings” has gone to Vimalakirti’s house in order to witness a debate between Vimalakirti and the Bodhisattva Manjusri, who is the Bodhisattva of Wisdom.

The “eight thousand bodhisattvas” that are being referred to here are considered to be beings who have trained deeply in the Mahayana approach to Buddhist practice, and their understanding is presented as being broader that the “limited” understanding of the Buddha’s disciples. In reading the scripture it is important to realise that it was written perhaps six hundred years after the time of the Buddha, and that the real Shariputra, for example, never said or did any of the things attributed to him in the scripture. The character of Shariputra is simply being used as a foil to help highlight the differences between the Mahayana view of Buddhist practice, and the practice of the Buddha’s disciples, (or rather the Mahayana’s view of the practice of the Buddha’s disciples). Similarly, the inclusion of the character of the goddess doesn’t imply that Buddhism teaches or believes that there really are such beings; it is just helpful to the story to have a character who has ‘powers’ that ordinary humans don’t have.

***

Whilst the Dharma debate between Vimalakirti and Manjusri had been taking place in Vimalakirti’s room, there happened to be a goddess there, invisible to everyone else present, who had been listening carefully to the proceedings. She now used her powers to make herself visible, and began to pay her respects to the bodhisattvas and the Buddha’s disciples by scattering heavenly flowers over them. The flowers that landed on the bodhisattvas just slipped off them onto the floor, but the ones that landed on the disciples stuck fast to them, and wouldn’t come off. The disciples frantically tried to shake and brush them off, but whatever they tried to do they couldn’t dislodge them.

When the goddess saw the disciples trying to shake off the flowers, she turned to Shariputra, who was one of the most senior amongst the Buddha’s disciples, and asked him why he was trying to get rid of the flowers. Shariputra replied, “I’m trying to remove them because they are not in accordance with the teaching.” Shariputra probably had in mind the monastic rules which prohibited the wearing of flowers or other adornments.

The goddess wasn’t impressed by Shariputra’s answer, and said, “You shouldn’t judge these flowers as not being in accordance with the teaching. Why not? Because in falling on all of you equally the flowers are practising non-judgementalism, which is in accordance with the Buddha’s teaching. You, on the other hand, are being judgemental, and that is not in accordance with the teaching. The Buddha’s teaching doesn’t have any problem with flowers, but you are judging them as unacceptable, just based on your own views and opinions. Because you have decided that the flowers are a problem you have become fixated on them and attached to them.”

The goddess is pointing out to Shariputra that the very fact that he wants to be rid of the flowers shows that he has an attachment to them. The goddess’s magical flowers highlight this attachment by only sticking to those who are attached to them. They are a bit like the dental paste that reveals any plaque that a person has on their teeth. The paste doesn’t put the plaque there, it just allows us to see where it is. Similarly, the heavenly flowers reveal who has a problem with the notion of adornments and who doesn’t. It’s as though the disciples have got their mental ‘hooks’ into the flowers, and won’t let go of them, and so the flowers can’t fall to the floor.

The scripture is contrasting the behaviour of the bodhisattvas, who have an open and flexible mind, with the behaviour of the Buddha’s disciples, who are portrayed as being constrained by a set of inflexible and rigid rules. The scripture is urging us too, to reflect on when we allow ourselves to be unhelpfully constricted by the many conventions which our society is shaped by. Of course some of these conventions, like all driving on the same side of the road, are really important, but others may be less useful, or even harmful. This is particularly so if we allow them to stop us from acting compassionately and generously, or if we give rise to attachments in response to them.

The goddess continues by expanding on her previous point, saying, “If you are so judgemental even after leaving home to become a monk, then it is you who are not in accordance with the teaching. To be in accordance with the Buddha’s teaching we must let go of judgementalism and attachment. Look at the bodhisattvas; they have already let go of judgementalism, and so the flowers don’t stick to them, they just fall to the floor.”

The goddess then turns to a further teaching that this incident with the flowers reveals. She says, “If a person is driven by fear, which inevitably accompanies attachment, then manipulative people will easily be able to take advantage of them. Similarly, all you disciples are afraid of the cycle of birth and death, and so your five senses (sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch), are able to take advantage of you.”

Fear accompanies attachment because, if we have something that we are attached to, we fear losing it. Similarly, if there is something that we hate then we fear its presence. If we fear losing something or fear its presence, then we can end up being driven to act in ways that cause harm in order to get or avoid it. We have been manipulated by the thing that we desire or hate. Similarly, if we fear the reality of birth and death, then we can latch on to things in a vain attempt to protect ourselves from it, or perhaps to distract ourselves from it. Our sensual desires and aversions allow our senses to take advantage of us.

Sensual desire, in other words craving anything that we perceive with our senses, is the first of what the Buddha calls the Five Hindrances. The goddess is saying that if we are afraid of birth and death itself, then sensual desire will overwhelm us. The second of the Five Hindrances is aversion, which is the other side of the coin; we want to be rid of the things we perceive, just as the disciples wanted to be rid of the troublesome flowers. The goddess is saying that fear leads to these hindrances.

The Scripture of Great Wisdom says the same thing the other way round. After saying, “With nothing to attain, a bodhisattva relies on Great Wisdom, and the hindrances fall away”, it says, “Without hindrance, there is no fear.”1

It doesn’t matter which way round we put it, fear and these hindrances go together. If we are afraid of our world we will never feel at ease within it, and so we will always be wanting to control the things we experience, either pulling them towards us or pushing them away. This is true not just of physical objects, but of relationships, status, reputation and many other things besides. On the other hand, as mentioned above, to the extent that we desire or hate things, to that extent we fear their loss, or fear their presence.

Shariputra is perhaps afraid of the effect on his reputation if people notice that he is adorned with flowers, which is prohibited under the monastic rules. This fear drives him to try to get rid of the flowers in any way he can, however undignified that might be. In judging the flowers as unacceptable, Shariputra has become caught up in an ideal of non-attachment. But attachment to non-attachment is still attachment.

Finally the goddess points out to Shariputra the importance of letting go of fear and desire, as only that way can we be at peace within the world we live in, and find the end of suffering. She says, “If a person manages to let go of their fear, then the five desires that arise from these senses will not be able to mislead them. When a person is still caught up in such fears and desires, the heavenly flowers will still stick to them. Once they have managed to let go of these fears and desires however, the flowers will no longer stick to them.”

The image of the Buddha’s disciples trying to shake the flowers off their robes may seem rather comical, but this encounter between (the character of) Shariputra and the Goddess is making a serious point about letting go of attachment. This can be very subtle. Shariputra thinks he is letting go of attachment in brushing off the flowers, but the Goddess points out that this view is itself based on attachment. We should look closely at our own views and opinions if we don’t want to get caught in the same way. Would the Goddess’s flowers stick to us, or fall off onto the floor?

***

Notes:

1. This translation is based on the official Sotoshu version (see below). The word ‘hindrance’ may not be specifically referring to the Five Hindrances as taught by the Buddha. The OBC version of the first phrase is, “In the mind of the Bosatsu who is truly one with Wisdom Great the obstacles dissolve.” It doesn’t include a translation of the sentence, “Without hindrance, there is no fear.” The OBC translation is based on one by D.T. Suzuki from his Manual of Zen Buddhism (see below), in which this sentence is also absent.

***

Sources:

There are several different translations of the Vimalakirti Sutra. The version of the story above is mainly based on the translation by Burton Watson:

Watson, Burton. The Vimalakirti Sutra. Columbia University Press, 1997. ISBN 9780231106566

See also the translation by Charles Luk (Lu K’uan Yü):

Lu, Kuanyu. Ordinary Enlightenment: A Translation of the Vimalakirti Nirdesa Sutra. Shambhala, 2003. ISBN 1570629714

Translations of the Scripture of Great Wisdom (Heart Sutra) referred to:

The official version of the Sotoshu, the Japanese Soto Zen Buddhist organisation:

https://www.sotozen.com/eng/practice/sutra/pdf/01/04.pdf

Suzuki, Daisetz Tetraro. Manual of Zen Buddhism. 1935.

The Liturgy of the Order of Buddhist Contemplatives for the Laity. Shasta Abbey Press, Mt. Shasta, Second Edition 1990, ISBN 0-930066-12-X

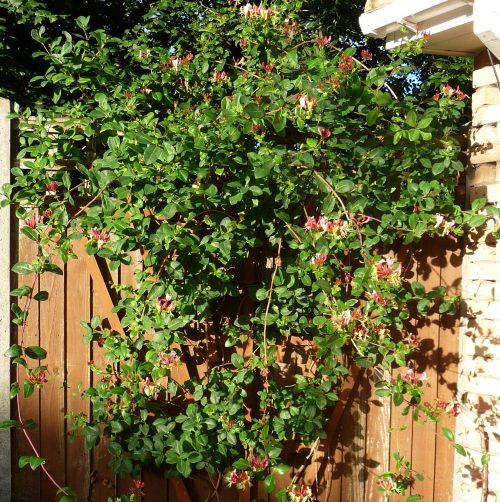

Some photos from the garden

With lots of wet weather in July and August our garden hasn’t needed very much watering.

We have a honeysuckle in the front border which has struggled every year until now, but this year seemed to like the conditions and has grown quite vigorously. Last year it just about managed two flowers, whereas this year it is quite covered in them.

Alms Bowl Requests

Donations of Food

Offering food is a traditional way to support a monk, and all donations of vegetarian food are most welcome. In particular:

- porridge oats

- peanuts or other nuts

- peanut butter

- fresh fruit and vegetables (except garlic or peppers)

- dried herbs

- cheese, eggs and yoghurt

Any other suitable items would also be appreciated.

Donations

The temple is dependent on donations for its continued existence, and any financial support you are able to offer is greatly appreciated. Details of how to offer support can be found on the Donations page of the website.

All donations are received with gratitude